Voices of the Wilderness Part 1

My Artist Residency Adventure in SE Alaska

You know the feeling that starts at your heart and permeates out to your fingers and toes filling your body with a warmth that tells you you’re exactly where you’re supposed to be? That’s the feeling I experienced during Voices of the Wilderness, a unique residency program that pairs artists with ranger districts in Alaska.

I matched with the USDA Forest Service Sitka Ranger District, which is in Southeast Alaska. Known for lots of rainfall and tall trees (spruce, cedar, and hemlock), I ventured into the temperate rainforest with an open mind and waterproof sketchbook–ready for anything and everything.

This journal entry lays out highlights of the wilderness experience. Stay tuned for a future post with artwork created from the overflowing inspiration!

First Things First

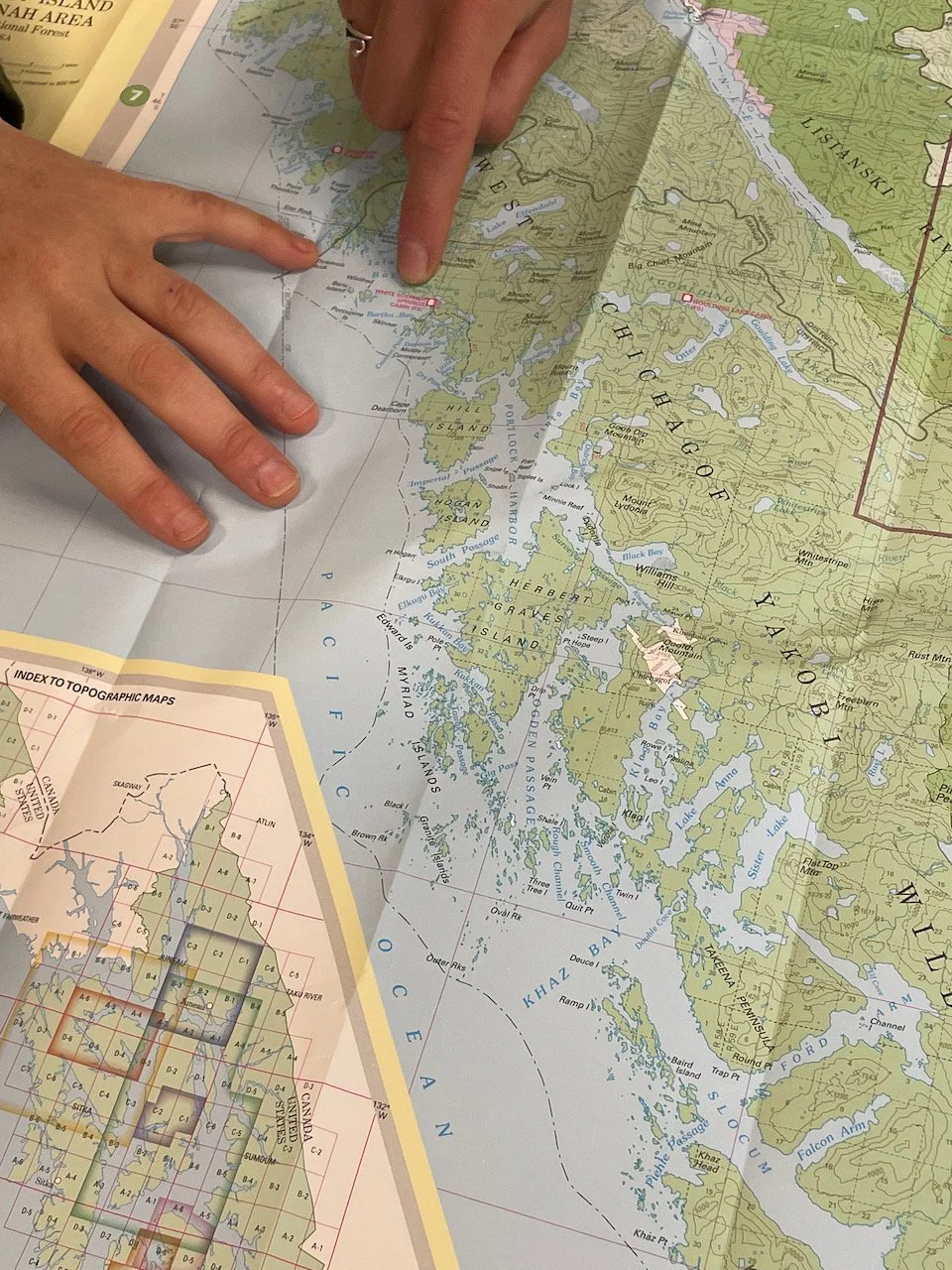

We (and by we I mean the rangers) mapped out a course to explore the northern West Chichagof-Yakobi Wilderness. I learned this area is called the ABC islands for Admiralty (1.7 bears per sq mile), Baranof (a chicken tender-shaped island where Sitka is), and Chichagof (the island whose western coast faces the Pacific Ocean). Yes, my phone still wants to autocorrect Chichagof to Chicago…but I digress.

To start off the 8-day excursion, we motored 7 hours from Sitka on a very fancy boat operated by a delightful and super knowledgeable captain. The routine was to anchor the big boat and then be dropped on land in the skiff (smaller boat). Tall boots are a must for wet landings! Once we made it to land, we would explore on foot. Sometimes bushwhacking, sometimes beachcombing, but always being bear alert.

Silly Skiff Names I Invented

No Skiffs, Ands, or Butts About It

A Hop, Skiff, and a Jump

Skiff to My Lou

Skiff Only

Tongass National Forest

Spanning 500 miles of Southeast Alaska, the Tongass National Forest is the largest intact temperate rainforest in the world. The forest is approximately the size of West Virginia with the Pacific Ocean on the west side and Canada on the east side. The Tongass National Forest has been the home of the Tlingit people for over 10,000 years and more recently the Haida and Tsimshian nations.

In conjunction with exploring the beautiful area I also started reading about its history in The Book of the Tongass. I can’t believe I had never heard of such a massive and important forest! Learning about the Tongass people, controversy, and conservation helped round out my in-person experience.

Muskeg Madness

I had never in my life heard the word muskeg before and I finally asked someone what on earth they were talking about. Turns out a muskeg is a “North American swamp or bog consisting of a mixture of water and partly dead vegetation, frequently covered by a layer of sphagnum or other mosses.”

Or as I would call it, an Alice in Wonderland booby trap.

After bushwhacking through a gnarly section of nontrail, the wide-open muskeg would be a welcome sight! Peculiar plants pop up out of the moss like Shore Pine, Roundleaf Sundew, Fernleaf Goldthread, and Russet cotton-grass. Truly a delightfully strange landscape.

Fun fact: sphagnum moss can hold fifteen to thirty times its own weight in water and is sterile so it was ground up and used in WWII to dress wounds.

Free Range Rangers

Needless to say, the plants throughout the trip kept me very entertained and curious. The rangers taught me about the five trees in the Tongass: Sitka Spruce, Western Hemlock, Cedar, Alder, and Shore Pine.

After glaciers retreated through the area, lichen started to break down rocks to create soil. Then, Alder trees popped up first because they can fix nitrogen. You can tell where an old landslide is because the bright leafy Alder trees fill in the rocky scar. Finally, the Sitka Spruce, Hemlocks and Cedars emerged to create the famous Old Growth forests of the Tongass.

I worked on identifying the different trees based on bark and branches with the help of my ranger buddies. While I collected plant specimens to draw, their job was to monitor human activity at campsites, collect soil samples, and record CMTs (culturally modified trees). One time we found a BMT: beaver modified tree!

Seaweed Shenanigans

Coming from tropical Hawaii, the unfamiliar Alaskan shoreline habitat felt very foreign. It was fun to explore tide pools looking for critters like Sculpins and Hermit Crabs. The deep jade pebbles contrasted the more muted tones of the landscape.

Most noticeably, the lurid tendrils of kelp and sea grass enchanted me. I started collecting small pieces to draw and ended up pressing some seaweed samples in my conveniently waterproof sketchbook.

As we walked around the isolated beaches we looked for plastic debris that had washed up. Beaches with lots of driftwood had the biggest stash of trash. It turned into an easter egg hunt and we collected all kinds of plastic and styrofoam trash. It was a reminder of how far-flung our impact on the environment is as a species.

Pops of Color

The action-packed trip through West Chichagof-Yakobi afforded me some pockets of time to draw and record my collected treasures. My primary goal was to record as many colors as possible.

At a glance, Alaska looks muted (especially compared to tropical Hawaii!). However, upon closer inspection, I found an array of gorgeous, natural colors in the miscellaneous artifacts I collected. From a crab carapace to a pinniped bone to the bright teal bacteria that decompose wood. So many beautiful colors!

Capturing the vibrant, nuanced colors using colored pencils turned into a really fun and satisfying exercise. Later in my trip, I discovered that Darwin used a similar reference book in the Galapagos. Great minds!

I will reference the colors as I make illustrations, patterns, and paintings inspired by this amazing experience.

The Importance of Wilderness

Reflecting on my time in West Chichagof-Yakobi Wilderness brought two words to mind: Awe and Humility.

Mirrored, majestic vistas delighted me. Unrelenting masses of hardy trees bruised me. A bubble-feeding humpback whale amazed me. Ice cold streams eased my throbbing feet unused to hiking in waterproof boots. Soupy muskeg muck sucked me into the earth. Shimmering seaweed delighted me with its unexpected stained glass grandeur.

My perception radar pinged almost nonstop during the 8-day sojourn. Wherever I looked, there was something intriguing to see. In addition to my sense of sight, my sense of touch also had a field day.

Slowing down to touch spongey sphagnum moss, slippery seaweed, and scraggly bear hair on a scratching post helped me feel connected to the vast array of natural phenomena.

We share the earth with a lot of plant and animal planetmates. Their adaptations to thrive in wild, harsh environments humbles me and piques my curiosity.

Connection is Key

Curiosity about our surroundings leads us to learn more about what interests us. In our day-to-day lives, most people embody disconnection. Disconnection from the ground (shoes), disconnection from food (plastic packages shipped from across the world), disconnection from other humans (screen time), etc.

Connection can start with a simple act like looking up and noticing something in our neighborhood trees. Or calling a loved one to hear their voice.

I am super grateful for the opportunity to jolt myself into acute awareness of my surroundings. My goal is to carry that heightened perception into my everyday life and continue to be amazed by the world around me.